Journey on the Trans-Siberian: Dear Kristina

This is part of a series about my journey across Russia on the Trans-Siberian railway, from St Petersburg to Vladivostok, in the summer of 2018.

The question “do you speak english” doesn’t usually confuse me. It’s not that I failed to understand your Russian accent, you just caught me at a bad time and a strange place.

Though I don’t fault you for that. You couldn’t have known I spent the night sleeping in the airport on a hard wooden bench, that I flew in the night before on a regional airline spun off Aeroflot with a two-star safety rating whose passengers were comprised of a Russian ballerina troupe, Asian tourists, and me.

Nor could you have known I was angry at myself for missing the chance to sleep in a first-class lounge because I exited the terminal without realizing. Or that I was looking forward to spending the 11-hour layover in Beijing by taking the train into the Forbidden City for a quick look before hurrying back for my flight to San Francisco.

The “Sling through Peking,” as I called it, was supposed to be a mini-adventure that capped off my trip across Russia aboard the Trans-Siberian railroad, which ended at Vladivostok and necessitated a stopover in Beijing, before heading direct across the Pacific.

It should be clear, I hope, why I paused and considered nodding “no,” since you approached me from the side as I was negotiating a Chinese ATM to dispense a day’s worth of yuan.

“Yeah, I speak English,” I said.

“Vi govorite po Ruskii? ” you asked, shifting from disbelief in finding an English-speaking person to wishful thinking of finding a Russian-speaking one.

“Da,” I said, with less hesitation this time.

Do you remember the relief washing over you? I saw it the moment I uttered my single-syllable affirmative, and understood you had reason to panic.

You were traveling to visit your dad in Seoul, and had a connecting flight in Beijing. The flight was leaving in just over an hour and you were lost.

A helpless girl is also unlucky if she finds herself in the world’s busiest airport knowing neither the language nor the departure terminal.

The sleeping arrangement during an overnight stopover in Beijing.

The sleeping arrangement during an overnight stopover in Beijing.

Sorry for judging you, but it worked in your favor. It’s the only reason I decided to help. That, and my estimation that helping you would take just a few minutes.

“You’re in the wrong terminal,” I determined after glancing at your flight itinerary and exchanging gestures with an airport employee.

“We’re in Terminal 3, you need Terminal 2,” I said, straining to find the Russian words, pointing at the sign for shuttle busses.

“Where? How? Will you show me? Please will you show me?” you said.

Our entrance into China was an unceremonious and brisk exit from the terminal towards the shuttle bus marked for Terminal 2.

“This will take you to Terminal 2,” I pointed.

“Are you sure? How will I know? Will you come with? Please don’t leave me!” you said.

What were you doing flying on your own…

Small deviation, I decided, but the Sling Through Peking will resume as soon as I help this girl find her way out of China.

We made small talk on the bus, as I split my attention between looking at outer Beijing and determining if I’m walking into a scam. “But what’s the angle,” I thought… You didn’t ask me for money, didn’t ask me to follow you anywhere, and you never touched my things.

Your flight was in about an hour. “Don’t worry, you’ll make it,” I said, in case this was real.

After arriving at the terminal I led you through security and right up to the China Southern check-in desk, where my responsibility turned to translating.

They needed to verify you’d be able to obtain a South Korean visa upon landing: Passport? You had it. Return ticket? You showed them your itinerary. Problem… They needed to see either a return ticket, or that you had enough money to purchase a return flight from Seoul. How much? One thousand dollars in cash, they said.

If they knew Russians earn an average of $437 per month, their expressions didn’t show it. But I knew, and couldn’t believe what they were asking until they repeated several times.

Despair came over you again as I translated.

Time to flight: 50 minutes.

We scrambled to find WiFi so you could contact your dad in Seoul for help. Moments later he transferred the equivalent of $1,000 to your bank account. (Most Russians use the same bank, Sberbank, which makes transferring money between people a 10-second task).

Back through security and to the check-in counter. You showed the agent and manager the bank balance on your phone. For a moment they seemed satisfied, but after a call to their superiors came a swift rejection: “No! Cash!”

Time to flight: 25 minutes.

Out through security and to the nearest ATM. The language options did not include Russian, so I took your card and tapped through the prompts as fast as the screen would respond.

“You have exceeded your daily withdrawal limit,” the screen said, even before asking for the pin. We tried again, but no change. (For some reason, I thought documenting the error screen would be useful.)

The ATM error.

The ATM error.

Off we went to the next closest ATM and tried your same bank card. This time we reached the pin entry screen, but it didn’t recognize the code. We tried a second time. On the third try… There was no third try. “Allowable pin tried exceeded.”

Another ATM error.

Another ATM error.

We would have taken the card out and run to the next ATM of dozens in the terminal, except… In the time it took me to photograph the error message (why?!) and explain its meaning to you, the machine made its own decision: “Time out. Card is kept for your protection.”

That was a hard one to translate.

(Some ATMs, it turns out, assume that if a card hasn’t been withdrawn within 10–20 seconds, then it must have been forgotten… so they eat the card.)

“It took your card,” I said, omitting the reason. You made involuntary sounds resembling the onset of hysteria. “Unfortunately, you’re not making the flight,” I said, failing to soothe you.

“That means we can calm down and take the time figure this out. There must be other flights to Seoul,” I said, and repeated again like a cool-down lap.

Beijing airport terminal.

Beijing airport terminal.

Back to the WiFi hotspot—some seats by the entrance of a business lounge that was leaking WiFi. You made calls to your dad. I called my wife to share a quick update and to get help researching instant money transfers from Sberbank to US checking accounts. If we could arrange a transfer then I could withdraw the $1,000 cash for you, I thought.

Part of my mind still cautioned this might be a well practiced and impeccably executed con game. That part was relieved to learn that instant transfers between Russian and US banks aren’t possible. Another part of me felt bad for having one less option to help, until you caught me up on the conversation with your dad:

“He has a colleague in Beijing,” you said. “He’ll come to the airport within two hours with $1,000. He said I am categorically prohibited from leaving the airport, with anyone.”

“So, then,” I said, taking note of the time, “let’s get tea.”

Drinking green tea in Beijing airport.

Drinking green tea in Beijing airport.

With green tea and snacks in front of us—the plate had a name but let’s not pretend we learned anything about China on this stopover—and our phones plugged in, I saw you at ease for the first time.

We spent an hour talking about this and that, your home city of Irkutsk, and my impression from my short stay there. I shared some photos, and we took one. I asked about your dad in Seoul and the reason for your trip, and wish I asked more because I still don’t understand.

It didn’t help my understanding when you went to the restroom and I noticed incoming calls from “Evgeniy –” on your phone. I messaged my wife to Google the name. (No results.)

Soon after you returned I steered the conversation to the person you’ve been communicating with—did you sense my doubt then?—which is when you clarified you’ve been talking to an associate of your dad the entire time; your dad was busy with work.

“So what,” I thought. “Her dad trusts his daughter to make it on her own, and trusts his associates to handle it if she doesn’t.”

But you couldn’t explain what your dad does for work.

“So what,” I thought, “Nobody in my family can explain my work, either.”

My worry about a scam had dissipated and was replaced with bewilderment: What is a girl who can’t tell “Terminal 2” from “Terminal 3” doing traveling on her own?!

That question never came out and neither did the answer. I probably uttered something about “learning experience” in my elementary Russian while throwing more Chinese snacks in my mouth.

Kristina and me.

Kristina and me.

It was late morning, about two hours since we met, when your dad’s associate arrived and spotted us in the crowd without difficulty. His hurried handshakes suggested he left work to do this favor, and he didn’t plan to linger. We hadn’t finished greeting before he handed you a wad of pink Chinese currency worth $1,000.

(In the midst of this I found room to smalltalk with Mr Beijing and learned he’s in China for a cryptocurrency mining company. That put me at ease, because it’s not human trafficking.)

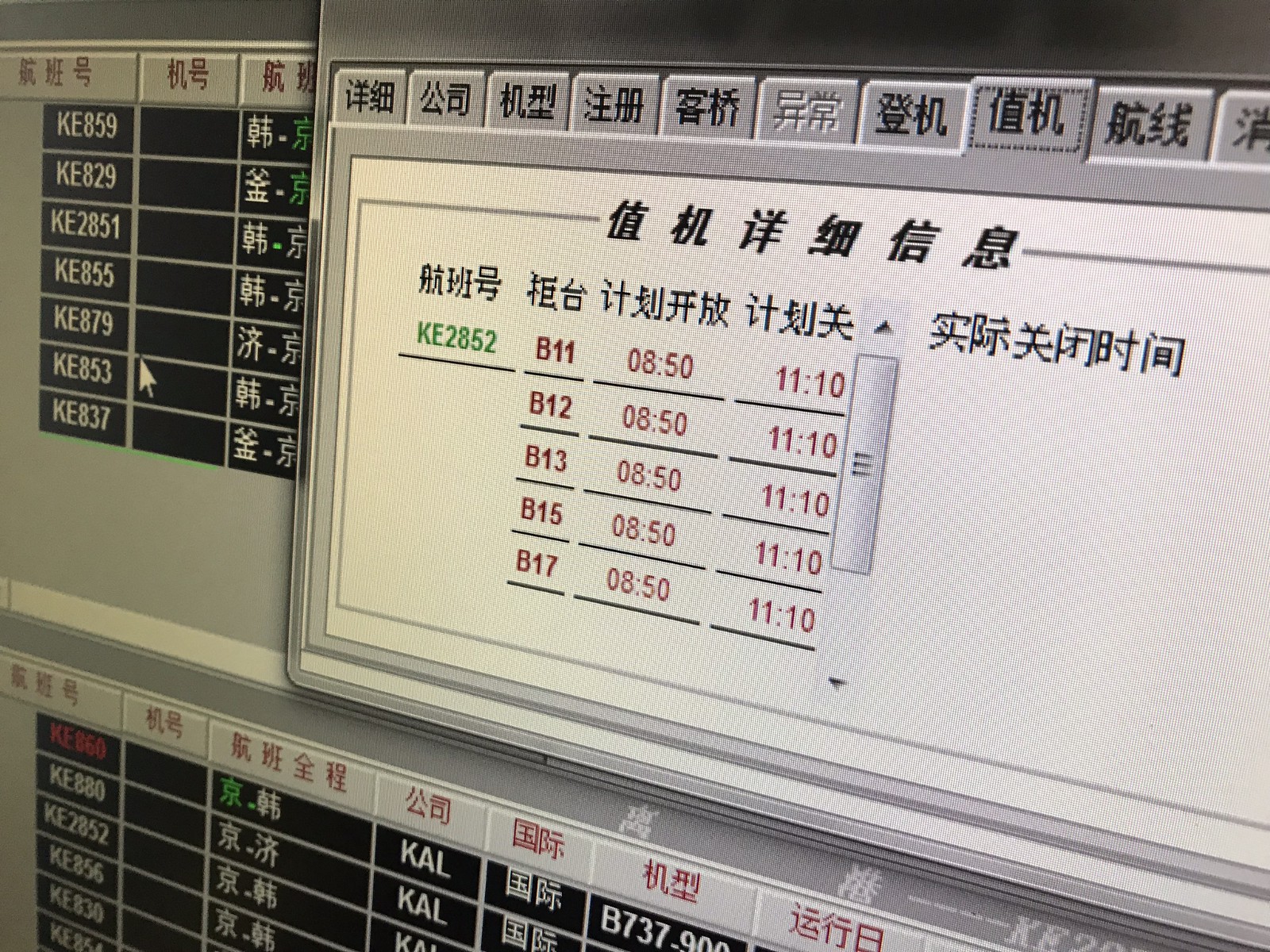

Timetable of flights to Seoul… I think.

Timetable of flights to Seoul… I think.

Embracing the change of pace, I rushed us past the security line and to the ticket counters, by which time Mr Beijing already found the next flight to Seoul—leaving in an hour—on his phone. We dashed to the Korean Air desk where Mr Beijing paid for the ticket, you presented your passport, and I translated.

The mention of visas and return tickets from the ticket agent unleashed a burst of broken Mandarin from Mr Beijing and fed-up English from me, with Korean grumbling on their side of the counter and Russian grumbling on ours. A minute later, the overwhelmed ticket agent let out a smile and we quieted. I heard the tinny croaks of a boarding-pass printer.

They never asked to see the cash.

Having performed his duty, Mr Beijing shook hands goodbye and disappeared.

Knowing better by now than to let you find the rest of the way, I walked you to the final security checkpoint for your gate area, and explained three times how to find your gate (“It’s just past this checkpoint; look for a sign with the number 15”), since I could not go through without a ticket. You expressed your gratitude for my help and promised to message me upon boarding.

Air China lounge in Beijing.

Air China lounge in Beijing.

With a massive sense of relief I made my way back to Terminal 3, found the lounge, gorged on food, showered, and reflected on the past few hours, days, and weeks. I took comfort in your message confirming you boarded your flight. You added: “Ti nastoyashi chelovek.” (“You’re a true human being.”)

The “Sling Through Peking” was an afterthought from the beginning. A consequence of arrival and departure times, of train terminals and airline routes. An unfit end to 19 days of connecting with the people of Russia, seeing their land, hearing their stories, and speaking their language. A way to fill the gap between my journey on the Trans-Siberian Railway and my return flight home, because I didn’t think someone from Siberia would be there to pull me into one last bit of adventure before the end.

Kristina, thank you for the perfect finale. I hope you are safe, and are exactly where you should be.

Next time, fly direct.

Air China plane in Beijing.

Air China plane in Beijing.

Previous chapter: The Seal Show in Irkutsk

Next chapter: The Packing List